Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Nick Bertozzi

posted April 28, 2007

A Short Interview With Nick Bertozzi

posted April 28, 2007

The cartoonist

Nick Bertozzi has two books out this spring, each with an impressive pedigree.

Houdini the Handcuff King is the first in the Center for Cartoon Studies' packaging deal with Hyperion Books, and allowed Bertozzi a chance to work with

Berlin's Jason Lutes. In an earlier form intended for publication at Alternative Comics, incidental nudity in what would eventually become St. Martin's

The Salon was previewed in a comic that ran afoul of Rome, Georgia authorities due to its accidental distribution to a pair of kids: what is commonly referred to as the Gordon Lee case after the charged retailer. For the purposes of an interview, neither book needs to be interesting in and of itself with all that going on, but both are, particularly

The Salon, a fantastic take on the origins of Cubism and a snapshot of life among the modernists in 1907 Paris. Next year Houghton-Mifflin will release a biography of Lenny Bruce featuring art by Bertozzi in collaboration with comics icon Harvey Pekar. I enjoyed my conversation with Nick Bertozzi; he seems like a swell guy.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I am kind of lost as to how The Salon developed; it's been around for quite some time. Can you walk me through how it got to this point?

NICK BERTOZZI: When

Tom Hart was starting to do

Modern Tales with

Joey Manley, I really wanted to be a part of that. So I developed it as a strip for

Serializer.net, when Tom started Serializer.net with Joey. I didn't know where the story was going to go, and it took about two months in, ten pages or so, when I realized I better do a lot more research, and I better do a lot more reference work, and better know where this story is going. At that point, I wrote it all down.

About a year into it, 50 pages or so into it,

Jeff Mason offered to publish it. So we were intending to publish it as a hardcover full-color all the way up to the point of July of '04. I think the book was done in May of '04. The first round was done. In April or May that year we put out the

Free Comic Book Day Alternative Comics #2 that got us

into so much hot water down in Georgia.

At that point a number of my friends and people I know in comics had received advances. Having a three-year-old at that point, and looking towards paying for school since we were sending her to private school, it would have been the height of irresponsibility to not at least test the waters and see what kind of advance I could get from another publisher. I really needed to get paid. And that's how it came to

St. Martin's, after extensive revisions with somebody I took on as an agent. I got the contract with St. Martin's I think two years ago, so this book's been a long time coming.

SPURGEON: That's not bad in terms of a standard book cycle, though. It might be a little odd for comics, considering you had a version of it done.

BERTOZZI: It's not strange at all, I know. But coming from comics where you finish something and it's out the next week. [laughter] It's a definite change of pace.

SPURGEON: You mentioned a strong editing process. What did that involve and who was involved in that with you? Was it someone at St. Martin's?

BERTOZZI: Yeah, my editor Michael Homler is the guy who bought the book. He did some edits toward the end that were very helpful in maintaining clarity and continuity. My agent Tanya McKinnon, who is also

Jessica Abel's agent and

Sara Varon's agent, she did extensive editing of the book prior to our selling it to St. Martin's, because she felt we should make it as strong as it could be. When you're that close to it, it's hard to see the forest for the trees. She really helped me fine tune it.

SPURGEON: Can you give me an example of something that was fine tuned?

BERTOZZI: I ended up dropping ten or so pages, and adding another 40. Going in to the words and making them very fine tuned to very large changes in the text throughout. Probably 90 percent of the book is different than the version Jeff would have published in 2004.

SPURGEON: What would be the biggest difference if someone were to read the two versions?

BERTOZZI: Everything. People would have scratched their heads a lot more. There were more sex scenes. One thing that was very helpful that Tanya brought was this sensibility of "You know, if you put too many sex scenes in a movie, you run the risk of diluting the power of those sex scenes. Sex scenes are like death scenes, where if you have more than one, it's 'here we go again.' Unless it's a porno movie." I definitely agreed with her in terms of the pacing. While the sex scenes weren't gratuitous, they weren't necessary. Those were pages I was changing anyway, and they were better served by something else. Like

[Georges] Braque taking a dump. Which also sounds gratuitous, but in my world it's not at all. It's a little character aspect that really, I think, puts the reader right in the world. I don't go back to that well five times. Which is my other problem. If I had done this book ten years ago, it would have been filled with every character on the toilet.

SPURGEON: A lot of sex and pooping in the previous version. [laughter] That is

a completely different book.

BERTOZZI: I'm bringing those up because they're the broadest examples. But there are many changes that were just continuity, changes I made where I explained a little more.

Jason Little helped me edit the book quite a lot and so did

Dean Haspiel.

SPURGEON: You said in one of your interviews that your interest in this time period had to do with giving yourself a project so you'd have to do the research and find out about it rather than something that was naturally a passion of yours. Is that a fair assessment?

BERTOZZI: Kind of. I wouldn't put it as either/or. It's something I'm definitely interested in and passionate about.

Cubism. I wasn't passionate about it, but I was passionate about understanding why it was important. One of the great things about comics, and not to go go too far from your point, but one of the great things about comics for me is that it's this wonderful catch-all for learning. It's like this great excuse to sit around and learn all the time. Learn how to draw better. Learn how to draw perspective. Learn how to model form. Learn about how to pace a story. Do this research about the modernists in 1907, and sink my teeth into that. It all flows back into my comics, so it's almost like I wonder sometimes since I wasn't a great student if this isn't the way I'm a great student. It all has to go back to my process of making comics getting better, becoming a better artist.

That's the long-winded way of saying I wanted to know why it was important to break the picture plane, because I didn't know what the picture plane was, even though I'd been to art history classes and heard this term bandied about. I'd been to studio classes. I was too afraid to ask the question in front of the teacher. What is the picture plane? Why is it important? Maybe they talked about it in one of the lectures but I was too stoned or hungover to pay attention.

SPURGEON: Were you inspired at all by historical fiction writers like Gore Vidal or historians who use novel-style narratives like Frederic Morton?

BERTOZZI: I can't say I'm a fan. I'm more of a fan where I find an author I like -- currently it's

Ian McEwan -- and I want to read anything they've done. So it's more I've read historical fiction and enjoyed it, but it's more because the author behind it is one I liked.

SPURGEON: There's a fantastic element to The Salon. What made you decide to use that device rather than stick to a more mundane, historical approach?

SPURGEON: There's a fantastic element to The Salon. What made you decide to use that device rather than stick to a more mundane, historical approach?

BERTOZZI: I thought it might be more interesting visually. [laughs] I thought there'd be more opportunities for hi-jinks and monkeyshines. One idea I had going into

The Salon since I was doing it on-line was that each page had to be like

[Jack] Kirby. You look at a Kirby page, he's either invented something, there's a fistfight or he's drawn a city underneath the moon or something like that. On every page. I imagine him picking up a page every time he's finished penciling it and he looks at it, and thinks, "There's the interesting thing on this page." And then he goes onto the next. That was my impetus for

The Salon, making it kind of fantastical, where there's these crazy sequences where somebody's falling through space. Or another crazy sequence where somebody's inside a famous painting.

This also had the benefit of getting me to redraw some of my favorite paintings, to get inside the compositional skills of somebody like Picasso or

Rousseau or Corbet. I heard a story that

Hunter Thompson, one of my favorite writers as kid, had typed out

The Great Gatsby. It flummoxed him. He couldn't figure out how this book was so great and moved him so much. I loved that. I often tell my students at

School of Visual Arts to do the same thing. You'll never understand Herge until you start drawing exactly like him. You'll never understand Kirby until you start drawing like him. I've done both Kirby and Herge, homages -- or rip-offs, if you want to call them that -- and I've learned way more than I had just looking at them. I'm somebody who has to take the engine apart and put it back together.

SPURGEON: The coloring in The Salon is really interesting. Can you talk about how you landed on that approach? Was it always intended to be like that?

SPURGEON: The coloring in The Salon is really interesting. Can you talk about how you landed on that approach? Was it always intended to be like that?

BERTOZZI: It was always intended to be two-colors, one for the foreground characters, and one for the backgrounds. There was the element of the blue

absinthe that runs throughout the book, it's important that that blue color surfaces only when the blue absinthe has been imbibed. I knew that I was going to be playing with that, the color was going to affect the story in that sense. I also wanted to play with that

Toulouse-Lautreccy kind of -- Toulouse-Latreccy?!? -- Toulouse-Lautrec-ish simple, bold colors against one another. It really helped the characters stand out against the background.

It also gives it a weird, I think it's not 100 percent of that time, but it's not 100 percent of our time right now, either. I'm hoping that it helps to suspend people's disbelief a bit more. Get people involved in that world. I knew every scene change would be a color change -- that would save me a lot of a time. I love

Herge, but there's nothing I hate more in comics than "Suddenly" and "Next" and "Time marches on" -- little captions that appear out of nowhere to tell you time has passed.

[Alfred] Hitchcock said that if you can't show that time has passed in film you're not doing your job right. So I was taking that to heart.

SPURGEON: Is there anything you want the reader to know by story's end? Or are you simply telling your story and letting the readers fend for themselves? Is there anything you would most wish for people to take away about those people, about that time?

SPURGEON: Is there anything you want the reader to know by story's end? Or are you simply telling your story and letting the readers fend for themselves? Is there anything you would most wish for people to take away about those people, about that time?

BERTOZZI: One thing in particular. I don't know if it's clear in the book, and if it's not I'm not worried about it. People that are involved in creative endeavors, I think what happens to a lot of people -- especially myself as a young man -- you get cowed into thinking that somebody like Picasso was this untouchable, legendary Olympian figure. You forget that he's just human. Rather than spending time working on your craft, or working hard on making yourself a better artist through technical learning, you think, "Picasso came out of the womb as this fully-formed artist. Everybody loved him off the bat. He's an incredible genius. He could draw, paint, sculpt anything he wanted. He could fashion anything in his mind's eye out of whatever materials were in front of him." People hear that, especially young people, myself included, and become dissatisfied with their own work and turned off from doing art. Or they go, "I'm a secret genius and nobody knows it yet" -- I know you've met people like this, Tom --"and if I am completely 100 percent original, I'm a true artist."

The truth is much different than that. Picasso was an incredibly gifted person, yes, but he also worked very hard. He was obsessive about his artwork, and his father was a painting teacher. That couldn't have hurt. The one thing I would love for people to take away from the book is how you think of some art movement like Cubism. It wasn't these two geniuses walking around Paris and out of a bolt of nowhere came up with a theory that changed art and pretty much the world. They were supported by a whole group of people. They spent a lot of time working before that. They came from very different backgrounds, which helped the process, and they were both intuitive in very different ways. I want to show that process, this art movement. So it's definitely historical fiction. I made up a lot of how they came up with Cubism. But it's far more human than it's this super-heroic legend that's grown up around them.

Like the Beatles. The two remaining Beatles will probably be the first to tell you they played a lot of music and they were lucky. People treat them like gods, but they're not. As a teacher of young people, I think it's really detrimental to walk away from working on your craft. You can always work on your craft. Even Picasso. To live in this fantasy world where you're suddenly appointed a superstar, it's not good for people at all. Myself included.

SPURGEON: Your other concluding scene focuses on the Steins. A lot of their earlier scenes are played for comedy, like the line they draw across their apartments.

SPURGEON: Your other concluding scene focuses on the Steins. A lot of their earlier scenes are played for comedy, like the line they draw across their apartments.

BERTOZZI: I didn't make that up!

SPURGEON: I'm sure you didn't. But after all of that high-energy fighting, the last scene is touching. I wouldn't have guessed you were going to go back to the plotline at all, so I was interested in what you might have wanted to impart there.

BERTOZZI: I don't know if I meant to impart anything. It seemed like a very truthful ending. Even when you've split with somebody and even when you're with somebody else, I don't think

Gertrude Stein was callous enough to not be moved by the fact that she might never see her brother again. He was someone she was very close to the first 30 years of her life. It was also to show the caring of someone like

Alice B. Toklas, to get a glimpse that she was somebody who would know how to take care of Gertrude in her weaker moments.

SPURGEON: Houdini the Handcuff King

's out, right?

BERTOZZI: Yeah.

SPURGEON: Has the feedback been positive?

SPURGEON: Has the feedback been positive?

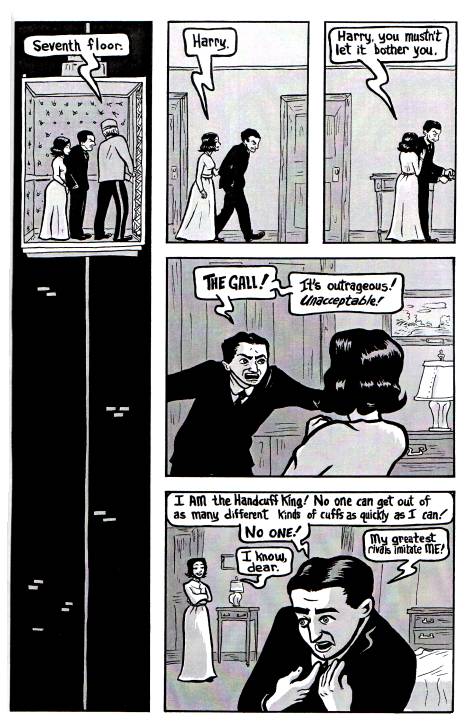

BERTOZZI: James Sturm sent me a great quote from a

Newsarama kids review of it, that there was a little too much kissing, but otherwise they loved it. They knew the kissing was integral to the story. People seem to like the art, they like the story, they like the fact that it takes place in one day. When I got it, I thought it was going to be really light. But it worked out great in the sense that like

The Salon it demystifies this amazing figure. Jason did a great job showing his range of emotions, and in retrospect it's the best way to tell his story: one trick. That's all you need to see to understand why this guy was so important. But people have been reacting well to it. They like it as a package. And people love Houdini. I haven't heard anything bad about it yet, and I'm happy about that. I've been catatonically ill with a cold this past week, so I haven't been able to enjoy the fruits of that.

SPURGEON: Is there anything intimidating about working with Jason as a writer, given that he's an artist and his own work is very precise?

BERTOZZI: [laughs] Yeah.

Jason Lutes is one of the best American cartoonists going right now. When

James [Sturm] gave me this chance to learn from Jason, I said, "Sure."

SPURGEON: Is there a specific something you learned?

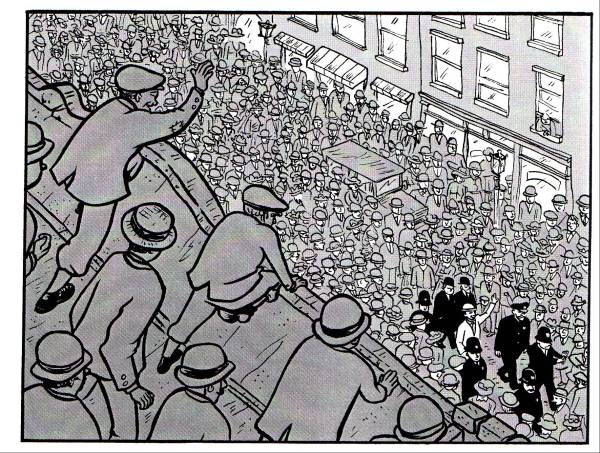

BERTOZZI: I know I've said this before, but his thumbnail layouts are the gold standard. I show them to my students. They're clear as a bell. They're tiny. They only get the most important information across. The thing that I really liked working with him is that he lays out his panels as two-page spreads, which is something I've never done. He thinks of the reading process while he's drawing. I think of the process, but I think of it in terms of a panel or a page. I don't think of two pages together. When you look at the Houdini book, there are vertical panels where Houdini and his wife are taking an elevator ride. That makes sense. An elevator ride in a vertical panel. It sounds simple, but who does that? Not only is it incredibly clear storytelling, but also incredibly subtle storytelling. I love storytellers of any kind, in any medium, that can tell you a story that works on a bunch of different levels but stays seamless. Once you're inside this universe they've created, you don't come out until you're done.

It's like the first

Star Wars. Maybe the acting's horrible, but it's a whole universe. When you're in a kid you're in that universe for two hours and you don't think of the outside world for two hours. In

Berlin or in

Jar of Fools, he keeps you inside that page. The composition of pages, the panel composition, the dramatic moments he chooses... it was intimidating to live up to that. I hope I was able to add... there are a couple of page I thought I could shine, one where you're looking over the shoulders of a bunch of people watching Houdini go down the street. I got to my 30th page of crowds in bowler hats, so I chopped off some of the panels so you'd only see Houdini over the shoulders of people on top of tenement buildings. In a lot of ways, it's Jason's book. I'm translating it. I'm not as good a draftsman as he is, but one of my strengths I hope is that I can capture a wide range of emotional content on people's face. I hope we made for an interesting collaboration. I would do it again in a heartbeat. It was so easy. I got the script. I got the thumbnails. There was not a lot of editing on it. James is so much fun to work with, and we've talked about working together at some point. I've been up to

CCS and he's fun to hang out with in addition he's great to work with. A great experience.

SPURGEON: Hey, can you talk about your Lenny Bruce book?

BERTOZZI: Yeah, I just signed the contracts yesterday. It's for

Houghton-Mifflin. It's for Deanne Urmy; she's the one that worked on Alison Bechdel's

Fun Home. So I'm really excited about that, because I love that book.

SPURGEON: How did that come about?

SPURGEON: How did that come about?

BERTOZZI: Dean Haspiel knows

Harvey Pekar very well, and they approached Dean to do this book. But he's working on that book with

Jonathan Ames for

Vertigo. It looks awesome. I've met Harvey a couple of time at convention. I wouldn't call it meeting. I got the brushoff from Harvey at conventions. [Spurgeon laughs] I lived with Dean when he got his first call from Harvey. It was hilarious being the fly on the wall during these long, rambling conversations.

I had a little trepidation in that I like

American Splendor, particularly when

Robert Crumb is drawing his stuff, but I like his more historical pieces anyway. I love Lenny Bruce, and hopefully there will be tangents about the history of American comedy, like

Bob and Ray, so I hope to draw that. What I was going to say is that I got the call from Harvey, and I wondered if he was going to be the kind of guy he is at conventions, where he doesn't want anything to do with me. But he charmed the pants off of me. I'm really looking forward to the book. He's really knowledgeable about comedy, and if he's half as knowledgeable as he is about jazz, then it should be a great book. There are some format tricks I'd like to throw in there as well. I haven't discussed those with my editor yet, so who knows?

SPURGEON: Is there a ballpark range when this will be out?

BERTOZZI: End of 2008. Which means I have to get it done by January.

SPURGEON: You have some work to do.

BERTOZZI: With the Houdini book, for an odd reason it turned out that Hyperion had to edit it for a very long time. It turned out that when I got the edits back from pencil, I had to do 70 pages of inking in one month. It was a lot of work, but it was good in a sense that now I know I can do that. I don't think the quality suffered.

SPURGEON: You don't want people to know you can do that!

BERTOZZI: Right. Strike that!

SPURGEON: Everyone will be writing this into their production schedules. "Get Bertozzi to ink."

BERTOZZI: [laughs]

SPURGEON: You said in an interview that there was a significant ramp up to publicity on The Salon. Anything we should we look for?

SPURGEON: You said in an interview that there was a significant ramp up to publicity on The Salon. Anything we should we look for?

BERTOZZI: A bunch of people I'd never been on their radar before. Art News. I got to do a bunch of illustrations for

The Believer based on it. I was happy to be in the company of

Charles Burns and

Tony Millionaire.

Wizard had

Houdini and

The Salon on the same page. Hopefully a

New York Times article. That was a lot of work to prepare for. [laughs] Not that he asked me questions that were hard, but he wanted to know every painting in the whole book. Who I was referencing. It had been a couple of years. I couldn't remember! There's that, and we're putting together a reading soon, at a bookstore I've never been to. And there's a

CBLDF benefit for the release party. That's been nerve-wracking in the sense I want to get heads in the room because I want to help pay for the $3200 a day in court costs.

SPURGEON: What are your thoughts about that whole affair? You've been living with it for a long time now.

BERTOZZI: You're calling from New Mexico, right? Where do you live? Taos?

SPURGEON: Silver City.

BERTOZZI: That probably used to be a lawless town. The situation in Georgia makes me think of that. I think the people get quotas and they have to try a certain amount of trials even if they're stupid and meritless. They have to go ahead and try them. I wonder if that's the same thing with a place like Silver City, which probably prospered because the lawmen could find mischief under every rock they turned over. Don't they have anything better to do in Georgia? Maybe they're not fans of this guy and his comic book store, but he's been in business of years and years. If you shut him down, people will get their comics from somewhere else. It doesn't seem worthwhile by any stretch of the imagination for anybody. It just seems like there's a zealous, opportunistic prosecutor that thinks they can make an easy name for themselves, or they have a bug in their bonnet about the guy and can't let it go. It doesn't help anybody, and that's the saddest part of it.

*****

*

Houdini the Handcuff King, Hyperion/Center for Cartoon Studies, hardcover, 96 pages, 0786839023 (ISBN), April 2007, $16.99

*

The Salon, St. Martin's Press, softcover, 192 pages, 0312354851 (ISBN), April 2007, $19.95

*****